Prior Interventions and Why they Failed

By Anthonia Momoh and Onyinye Ngene

As stated in the British Council’s 2011 Next Generation report on Nigeria, “Youth, not oil, will be the country’s most valuable resource in the twenty-first century”. It is safe to say that Nigeria has an abundance of this resource. The country’s population is young, with a median age of 18.1 years, growing at 2.59 percent.[1] The benefits of this resource could be enormous if Nigeria can create high-paying employment and opportunities, positive economic growth, improved healthcare, and a revamped education system. However, this is not the case, as youth unemployment remains a significant concern.

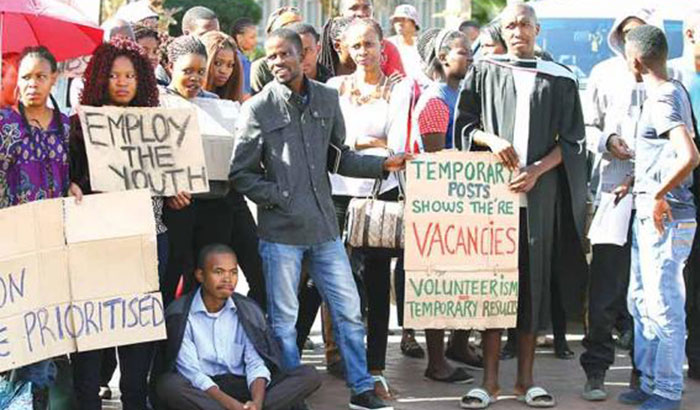

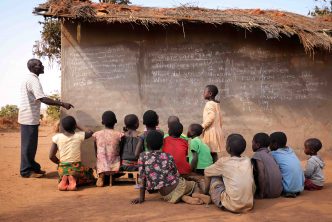

According to the 2020 Labour Force Survey, published by the National Bureau of Statistics, the unemployment rate among young people (aged 15 – 34) in the second quarter of 2020 was 34.9 percent, up from 29.7 percent in the third quarter of 2018. The youth underemployment rate was 28.7 percent, up from 25.7 percent in the same period.[2] These rates were the worst compared to other age groups in the labour market. On human development, Nigeria has a score of 0.534, ranking 158th out of 189 countries and territories.[3] This score puts the country in the low human development category. Going further to youth development specifically, Nigeria had a score of 0.514 in the 2016 Global Youth Development Index, ranking 141st out of 183 countries. In the domains of education and employment and opportunity, the country ranked 157th and 158th, respectively.[4]

The youth are the engine for economic growth and development, but this engine needs oil. Youth unemployment is driven by several factors which include the country’s insufficient job creation capacity, weak education system, considerable skills mismatch in the labour market, corruption, challenging business climate and many others. There is an intuitive link between youth unemployment and youth restiveness which manifests in the conflicts and social unrests across Nigeria. Goldin et al. (2015), in the 2015 Solutions for Youth Employment report, suggests several links between youth unemployment and crime, national fragility, economic insurgency and increased youth extremism.[5] As such, the dangers of leaving this problem unchecked are already costly for Nigeria.

In addressing the issue of youth unemployment in Nigeria, different federal government administrations have taken a range of approaches focusing on labour demand, labour supply and labour market interventions (Abah, 2017). The National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP), for instance, was set up by the Olusegun Obasanjo administration in 2001 to replace the Poverty Alleviation Programme (PAP). The programme had five main areas, four of which had employment components (Wohlmuth et al., 2008). Additionally, the Goodluck Jonathan administration introduced the Subsidy Reinvestment and Empowerment Programme (SURE-P) in 2012 with interventions in infrastructure development projects, social safety net projects, vocational training schemes, Community Services/Women and Youth Employment (CSWYE) programme, Graduate Internship Scheme, and others.[6] In 2016, the Muhammadu Buhari administration set up the N-Power programme – a national social investment programme – to empower and improve the employability of young people (aged between 18 and 35 years) through skill development.

Some of the other unemployment alleviation programmes initiated by the federal government over the years include Operation Feed the Nation, Green Revolution, National Directorates of Employment, National Accelerated Food Production Programme, and many others. However, despite these interventions, youth unemployment persists, and unemployment generally has continued to increase, rising from 10.4 percent in 2015[7] to the current rate of 27.1 percent. Why have these programmes failed to impact significantly on youth unemployment in Nigeria?

This poor outcome is attributable to several factors. There is the challenge of weak policy conception. The intended beneficiaries of these unemployment alleviation programmes – the youth – are not typically consulted before their design and implementation. In a 2019 study of government-assistance programmes and their impact on unemployment reduction in Nigeria, several entrepreneurs stated that the interventions did not address their interests; instead, political considerations appeared to be paramount.[8] This challenge results in a vague understanding of the problem at hand and translates into poor targeting and implementation of the solution. For instance, the unemployed youth are typically lumped together in these interventions when, in fact, their situations differ based on their skills and capabilities, location, educational level, gender (Akande, 2014).

These programmes also suffer from a poor management structure. The approach taken by the government lacks coherence, with different ministries and government agencies managing the programmes in isolation from one another. This uncoordinated structure limits the ability of these programmes to deliver impact. This lack of synergy was conveyed in the refusal by the Bank of Industry to fund applicants under the National Enterprises Development Programme because it was not consulted during the conception stages of the programme (Abah, 2017).

Nigeria’s attempts at programme implementation have been, at best, inefficient resulting from a duplication of programmes targeting the same group of beneficiaries. Successive governments set up these programmes in isolation. The programmes do not complement or continue from their predecessors’ initiatives. Successive governments, even when they are from the same political party, typically scrap or replace existing programmes, without any impact assessment to understand reasons for the sub-optimal performance and how to improve the probabilities of success.

Failure to plan for the long-term is the bane of many government interventions. The programmes suffer from the short-termist challenges of democratic governments. They are typically prescriptive without measures to implement long-term policies, address the root causes of youth unemployment, and stimulate labour-intensive growth (Abah, 2017). According to Akande (2014), youth unemployment programmes have not yielded the desired results because training is often not accompanied by soft loans, which could be used as start-up capital by graduating trainees to facilitate their integration into the labour market. Also, Nigeria needs structural changes to comprehensively address labour supply and demand mismatch, and other macroeconomic challenges in the country.

Furthermore, these programmes are poorly monitored and evaluated. Without meticulous monitoring and evaluation of the various interventions, it is difficult to know which programmes are delivering results, which are not working and the reasons for the outcomes. Thus, there is no official way to understand what components to improve on.

Lack of adequate funding is another reason for the failure of some of these programmes. The complexity of this point was exemplified by the National Accelerated Poverty Reduction Programme that spent most of the available funds on overhead and administrative costs in offices across the country. This sub-optimal choice resulted in inadequate funding available for programmes. To ensure effective implementation, the government needs to ring-fence the programme funds from the ones spent on administration.

Various federal government administrations introduced several programmes and initiatives aimed at alleviating the problem of youth unemployment in the country. They have, however, not had any remarkable impact on the situation, falling victim to issues such as weak policy conception and management, lack of funding, inadequate monitoring and evaluation, and many other challenges.

The government has a role to play in addressing youth unemployment in the country. Going forward, to ensure that these efforts translate into results, the programmes must be shaped through extensive consultation with stakeholders and beneficiaries, adequately targeted and managed, designed to complement other existing interventions, and coherently managed. Additionally, the government must monitor the programmes to assess their impact, and also implement them alongside longer-term structural changes in the country.