Finding a sustainable solution to the Herdsmen/Farmers Crisis

Dr. Iro Aghedo

As climate change causes more Herdsmen to migrate south in search of greener pastures, population growth is causing southern farmers to explore and cultivate southern lands that were once freely grazed by these nomadic herders. This results in inevitable clashes as both sides try to survive.

Background

Nigeria is fighting several domestic wars on different front-lines. In the last two weeks, nomadic herders’ violent activities in the South-West region have dominated media attention. The invasion of armed herders and the efforts by resisting farmers have led to several deaths, destruction of property, and ethnoreligious tensions and generated contentious politics between the federal government and the subordinate units. This hasn’t always been the case, as the relationship between nomadic Fulani herders and sedentary crop farmers were often cordial and harmonious. As in much of Africa, pastoralists and hunter-gatherers have engaged in mutually beneficial networks for over 5000 years. Recent conflicts between these two groups are caused by poor government policies that undermine the groups’ interests and render them vulnerable (Campbell, 2004).

Also, poor adaptation to climate change has been a core driver of livelihood insecurity across the African Sahel region, especially for “livelihoods that depend on natural resources, such as farming, fishing, and herding”. In Nigeria, relations between farmers and herders have been peaceful and mutually rewarding for thousands of years, even though there were a few skirmishes. In the last five years, the incidence, scale, frequency, and lethality associated with herders’ violence have increased tremendously. This has left many wondering how and why the situation degenerated to the level of everyday violence. This edition of Nextier SPD Weekly examines the metamorphosis of grazing violence and highlights how the escalation can be addressed, especially now that President Buhari has appointed new service chiefs.

One Violence too Many

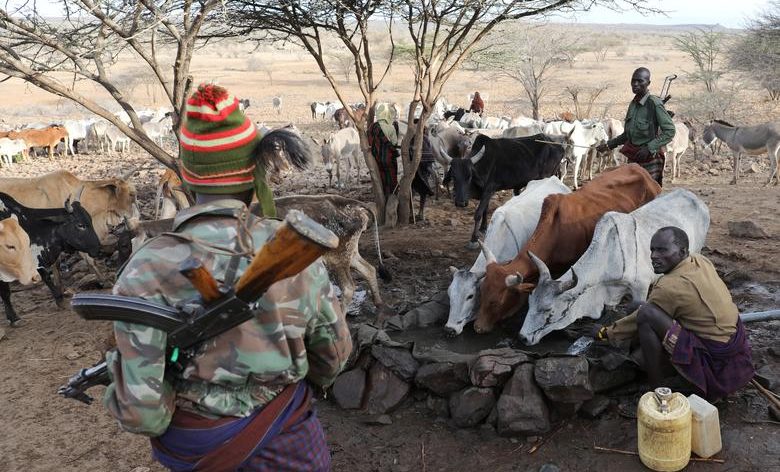

Pastoralists in Nigeria are classified into three major groups: sedentary pastoralists (those who rear their livestock in one place); transhumance pastoralists (those who go about with their livestock for a short time, sometimes seasonally); and nomadic pastoralists (those who traverse the long-distance with their livestock sometimes across international borders). In the pre-independence era, livestock vulnerability emanated largely from natural disasters such as erratic climatic patterns, fire incidence, and disease outbreaks. But from the 1960s to the late 1970s, individual land ownership regimes posed a formidable threat to livestock herding. The colonial administration also came up with tsetse control measures, including veterinary medicines, to curtail the danger of tsetse-related diseases in the humid regions. This further aided the migration of herders and their livestock south-wards.

In recent years, grazing violence has assumed frightening dimensions. Attacks on farmers take various forms, such as the invasion of farms, laying of ambush, setting farms and houses ablaze, robbery and rape. On the flip-side, attacks on herders take the forms of cattle rustling, poisoning of livestock, the barricade of routes, and farming on reserved lands. The frequency and severity of the conflicts along regional, religious and ethnic lines have intensified, especially since 2015. These clashes are carried out using sophisticated weaponry such as semi-automatic rifles, improvised explosive devises, axes, bows and arrows, daggers, machetes, cudgel (Sanda), and petrol for setting property ablaze.

Arresting the Violence Metamorphosis

Efforts to manage the herder-farmers’ conflicts have not been effective hence the regular reports of deadly clashes. Some daily measures are needed to reduce the menace drastically. First, there is a need to depoliticize the management of grazing violence. Public policies addressing this issue should objective to ensure peace in ethically and religiously divided societies. Sadly, this principle of neutrality does not seem to have been upheld by the Nigerian government in managing grazing violence. The body language of the government is clearly in favour of the herders. Besides, Buhari and key members of the Buhari administration and security officials are predominantly of Herdsmen ethnic background. These government officials have openly supported the herders by saying that their attacks are provoked by the farmers’ taking over grazing routes. Worst still, several public policy proposals have been made to support the herders to the detriment of farmers, such as the RUGA and cattle colony. On account of these policy proposals’ divisive nature, they have not seen the light of day. Government’s favourable disposal to the herders’ interests seems to have promoted a culture of impunity of violence among the pastoralists, leading to resistance by the farming communities and their allies, as recently witnessed in Oyo State and Ondo State.

Second, there is an urgent need to address the pervasive spread and use of illegal arms. Grazing-related violence has become deadly in recent years because many illicit weapons are in the hands of herders, cattle rustlers, and even farmers. Such weapons are deployed at the slightest provocation leading to deaths and severe injuries (Duquet, 2009). When the herders and the farmers were armed with “sticks”, cudgel, bowls, and arrows, the deaths and injuries associated with their activities were minimal. Thus, there is a need for the necessary security agencies such as the Police and the Army to effectively mop up deadly weapons in the hands of herders, farmers, and rustlers.

Third, the government and cattle industrialists should commission security and development firms to research the feasibility of large-scale ranching in Nigeria. Some cattle entrepreneurs, including President Muhammadu Buhari, have ranched their cattle. Other owners of large herds should follow suit. Such a commissioned project should include the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria and other similar groups. Sensitization on the need to embrace large-scale cattle ranching as done in Europe should be an integral part of the project. This will mitigate cattle rustling and herders’ clashes with farmers and result in better herds’ better productivity since they will no longer walk long distances searching for pasture and water.

Finally, local vigilante groups should work in synergy with herders for mutual protection. The practice of vigilantes protecting the farmers and the herders protecting themselves and their herds is not a good one. Collaborative efforts will enhance mutual understanding among them. In doing this, Nigeria has a lesson to learn from the South African Hemmersbach Rhino Force anti-poaching rangers who have deployed a similar strategy to protect the rhinos.

Conclusion

Through its security apparatus, the government needs to deploy more effective strategies of addressing grazing violence in Nigeria. Some of these means include the depoliticisation of grazing policies; mopping up of illicit weapons in the hands of herders, rustlers, and farmers, commissioning research to explore modern ways of cattle ranching, ensuring that local vigilantes and herders work together for mutual protection and peace.