Dealing with vaccine apathy to get the Covid-19 vaccine to those who need it.

By Moji Obasa

As Nigeria makes efforts to recover from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, there remains the challenge of dealing with indifference towards the vaccine by a large number of Nigerians.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak disrupted the world’s socio-political and economic order in a way that has never been witnessed since the 1918 Spanish Flu. Governments imposed measures such as total lockdowns, stringent border controls, travel bans, and masks mandates to curtail and contain the unfettered spread of the virus while easing the unprecedented burdens on healthcare systems. Therefore, it is not surprising that governments and citizens alike are eager to put the COVID-19 pandemic behind them and return to normalcy. The partnership of governments like the U.K. government, development partners, and pharmaceutical companies brought hope to the world as the announcement of an approved vaccine filled the air by November of 2020.

The announcements ushered a scramble by wealthy nations to secure doses. It became apparent that without deliberate effort at price-fixing and heavy subsidising, under-developed countries might not be able to access these vaccines. This situation led a coalition of humanitarian organisations and manufacturers to create the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative to accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines.

Nigeria’s History with Vaccines

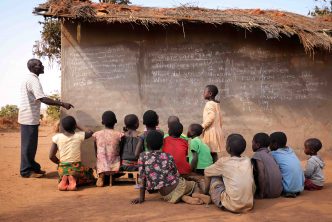

In 1996 the Pfizer Trovan (a meningitis vaccine) clinical trials in Kano resulted in the death of some of the participants as it was carried out without following acceptable procedures (McNeil, 2013). This sad event frayed the confidence in vaccines, especially in Northern Nigeria, even after two decades (Jegede, 2003). The result of this can be seen in the delay in eradicating polio in Nigeria as the populace boycotted the vaccine (Ghinai et al., 2013). It wasn’t surprising that in Kano, there was a high level of apathy towards the COVID-19 vaccines (Ihyongo, 2021). The situation has been made worse by the level of illiteracy in the region, so for any meaningful vaccine roll-out to take place, there needs to be a robust strategy to tackle vaccine hesitancy in a way that will address the concerns of these communities.

The question of Covid-19 roll-out strategy

With the allocation of 16 million doses of the vaccine from the COVAX initiative in March 2021, the country received the first batch of 4 million doses of Oxford’s Astra Zeneca, making the her one of the first beneficiaries of the initiative. Upon receiving this vaccine, the Minister of Health stated that there “is a very intricate distribution plan that has been set up by the federal ministry of health and organised by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency. I am satisfied that the National vaccine deployment plan (NDVP) will be properly executed and the advisory of starting with frontline health workers, the elderly and the vulnerable population will be adhered to” (WHO Press Release, March 2021). Like the minister, several relevant government officials consistently assured of a plan to roll out the vaccine even though this plan is yet to be made public.

The need for a coherent and consistent national plan

There has to be a coherent nationwide strategy that would both be applied uniformly across the country. The disparity in strategy implementation is detrimental to public morale, public trust and widespread public confidence needed to ensure herd immunity. Transparency in the processes, from sourcing of the vaccines, countries of origin, numbers allocated, criteria for allocation to agencies handling the vaccines at both local and national level is crucial.

The inconsistency in rolling out the vaccine can be seen in the roll-out by the Lagos state government. The state government announced that health care workers would be prioritised to receive the vaccine. However, on the day the state rolled out the vaccination, a septuagenarian received a vaccine on what appeared to be on the basis of his age. Right off the bat, Lagos’s roll-out implementation prioritised the vaccination of older citizens.

This reemphasised a concurrence in administering vaccines to identified groups rather than the staggered approach announced. However, this lack of consistency across the nation, within states and the variation across centres further confuse the populace.

Effective Strategic communication

Strategic and nuanced messaging sensitive to the peculiarities of different communities must be employed to encourage the public to partake in the vaccination exercise and overcome public scepticism. The roll-out of the AstraZeneca vaccines in Nigeria coincided with a temporary ban on the vaccines in the E.U. and some other countries (Yang, 2021). However, in the wake of the understandable scepticism that arose about the safety of the vaccine, there was a marked absence of concerted efforts at the national level to create an awareness campaign on the rationale behind the continued administration of the vaccines in Nigeria (Adepoju, 2021). Targeted messaging with easily accessible infographics in local languages should be disseminated both traditional and new media to address misinformation and myths surrounding specific vaccines. The urgency for improved communication about covid-19 vaccines becomes even more imperative in the wake of recent concerns raised about the Johnson and Johnson Covid-19 vaccines in recent weeks.

The government must publicise the quality assurance processes for AstraZeneca and the Johnson and Johnson and any other vaccines administered in the nation. They must also put in place robust surveillance systems to monitor vaccine efficacy and safety and report any adverse events.

Technology as a tool for vaccine access and gatekeeping

Recently, the NPHCDA announced an online registration portal to sign up for the vaccine. This system is expected to provide crucial demographic information for vaccine prioritisation, but it fails to recognise that a huge population of the country lack access to the internet. The inefficiency of this system is even made more evident as some report indicated that members of the public got the vaccine without registration on the portal, while a lot of those who registered are yet to be contacted for the next steps.

Beyond the challenges with the online platform, there is no evidence of a plan to accommodate persons who lack formal identities as required by the online platform as a sizeable chunk of the population do not have government-issued identification. It is, therefore, important that demographic information regarding those vaccinated is thoroughly studied to find out the factors that inform the likelihood of vaccination and, conversely, factors that underscore non-take-up of vaccines to inform policy decision-making better. To mitigate this challenge, especially in the absence of a more recent accurate census data, information from government agencies can provide an overview of the demographic composition of the population, which can help determine how the vaccines will be allocated and accessed by the public.

Creatively connecting with the grassroots

It is laudable that high profile figure like the president, governors and senior public officials got vaccinated publicly. It is yet to be seen how such public gestures will translate to wide acceptance. For example, while the governor and cabinet members publicised their vaccination in Kano state, it did not translate to high vaccine uptake numbers in the grassroots. More work is required to allay the fears within the communities. One way to tackle this would be to engage religious leaders within the state to help raise awareness and allay fears. Religious and traditional leaders in these areas provide a way out as they wield influence among the populace that can be leveraged to vaccinate the public against COVID. An excellent example of this has been demonstrated by how public health officials worldwide have been working closely with religious leaders to ramp up support for the vaccination plan and debunk widespread misconceptions about vaccines and the virus itself. In the wake of the holy month of Ramadan, Islamic leaders in the U.K. and the U.S. have been using social media, virtual town halls and face-to-face discussions to sensitise their congregations that it is acceptable to partake in the vaccination for the coronavirus during the month (Fam,2021). A similar campaign on a massive scale in the Muslim dominated northern Nigeria would prove beneficial in encouraging higher vaccine uptake rates.

The need for collaboration

Tackling COVID-19 ignited unprecedented public-private collaboration across organisations, industries, academia, and governments and irrefutably demonstrated the value of partnering to deliver new solutions and improved outcomes. The government of Nigeria should aim to work in tandem with non-governmental organisations to solve the challenge with vaccine roll-out. For example, during the lockdown in Nigeria, the government worked together with a private-sector task force, the Coalition Against Covid-19, CACOVID, to procure relief materials, protective gears, isolation centres, testing kits etc. Such collaborations should continue as the pandemic enters into the vaccination phase. Telecommunications providers can also provide data or shortcodes to register interest in getting vaccinated, report adverse effects where applicable, etc.

There is also a need to use these relationships to register people in the local communities without access to the internet, phones and other technologies required for the online registration.

Given the limited resources available and the less optimal state of health care systems in the country, to embark on such a huge project of vaccinating 40 per cent of the population by the end of the year as targeted by the government, all hands must be on deck.

Conclusion

Although Nigeria is currently grappling with various financial challenges occasioned by the pandemic, the health of its citizens should remain a priority. As the world begins to recover and return to some form of normalcy, Nigeria, along with other resource-poor countries, must ensure that she is not left behind in the fight against the COVID-19 virus.

Moji Obasa is a lawyer with more than a decade’s experience, a consultant and an advanced interdisciplinary researcher in the intersections of public health, anthropology, law, philosophy, policy and governance. She holds an LL.B. Law (Ife), LL.M., Biotechnology Law and Ethics (Sheffield) and an M.Sc. Bioethics (Leuven). She is currently completing M.A. in Cultural Anthropology and Developing Studies and working on a doctoral degree.