By Anthonia Momoh

Nigeria has abundant human resources with a population of over 200 million people that is estimated to double by 2050. This population is potentially a huge market as it constitutes about half of the peoples of West Africa. However, Nigeria’s economic outlook is bleak. In 2019, Nigeria’s population grew by 2.6 percent, which was faster than the real GDP growth rate of 2.3 percent. With the slow recovery from the 2016 recession coupled with the slowdown resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria’s economy will contract by about 3.4 percent in 2020.

A youthful population should be an asset to Nigeria. As of 2016, almost 70 percent of Nigerians were below the age of 30, indicating a young population (United Nations (UN), 2017). However, Nigeria is yet to feel the impact of this group as youth unemployment (for Nigerians aged between 15 and 34 years) was 34.9 percent in Q2 2020, up from 29.7 percent in 2018. The same data indicates that youth underemployment rose from 25.7 percent in 2018 to 28.2 percent in 2020. Of all age groups in Nigeria, the youth are worse off as their unemployment rate is higher than the national average of 27.1 percent in 2020.

Youth unemployment results from a myriad of factors. The most significant of these factors is ‘jobless growth’, which is a situation of economic growth without concurrent job creation. In 2018, while over 5 million Nigerians entered into the labour market, the economy was able to create only 450,000 jobs. Consequently, the number of unemployed Nigerians increased by 4.9 million in 2017 to a total of 20.9 million in 2018. The other significant factors driving youth unemployment include the population growth rate, poor educational system, difficult business climate, and regional disparities (Bandura and Hammond, 2018).

Unemployment and underemployment will likely worsen in Nigeria as the growth of the labour force outpaces the population growth rate. According to a 2019 World Bank report, Nigeria needs to create 30 million new jobs by 2030 to maintain the current employment rate. As stated by Runde and Hammond (2018), Nigeria must create about 40 to 50 million jobs to keep pace with its growing population.[v]

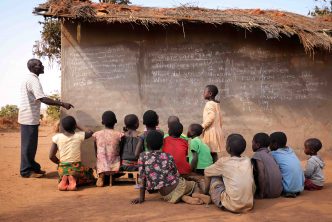

The impaired state of Nigeria’s educational system contributes to youth unemployment. According to UNICEF, Nigeria has the largest number of out-of-school (OOS) children in the world. One in every five of the world’s OOS children is in Nigeria. This challenge exists even though primary education is officially free and compulsory. Of the 6.9 million graduates in Nigeria’s 2020 Labour Force Survey, 2.7 million were employed full-time, while 2.8 million were unemployed (National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2020). The statistics hint at the problem of unemployability. Deficient school curricula and inadequate teacher training result in a disparity between the skills taught in schools and those sought by employers.

The business environment in the country is not conducive for entrepreneurs and investors. Businesses have to contend with insufficient infrastructure, crime and insecurity, non-transparent economic decision making, lack of effective judicial due process, and corruption.[vi] Access to finance is a prevalent issue. Of the 840 micro, small and medium-scale enterprises (MSMEs) surveyed in Nigeria, only 31 percent obtained a loan from a bank or microfinance institution.[vii] A 2018 survey showed that 36.8 percent of Nigeria’s adult population are financially excluded.[viii]

Various governments in Nigeria acknowledged the need and urgency required to tackle youth unemployment. The range of policies and programmes from the 1960s is evidence of this understanding. Without an official evaluation of the various interventions, it is difficult to assess the impact of these interventions. A review of the trendline of GDP and unemployment rate leaves much to be desired.

The failure of the policies and programmes to address the unemployment problem in Nigeria can be attributed to several factors. Abah (2017) attributed the failure to the inadequate conceptualisation of the programmes and the lack of a long-term perspective. Akande (2014) attributes the failures to weak management of the programmes worsened by inconsistency, duplication, and lack of synergy between the different parties involved in the implementation. Also, inadequate funding, poor targeting, and patronage politics contribute to the inability of these programmes to significantly reduce youth unemployment.

A whole-of-government approach is required to solve the youth unemployment problem in Nigeria. The diverse ministries, departments, and agencies must work together to provide a shared solution to the unemployment challenge. The private sector and civil society organisations – and the youth themselves – should devise a framework for collaborating with the government to identify the root causes of the problem and the potential solutions. Nextier, with support from the Think Tank Foundation, collaborated with the Centre for the Study of Economies in Africa to convene such a session in 2014 and 2018.

Policy interventions should aim to boost private investment and stimulate demand to expand economic activity and increase the available job opportunities. To this end, Nigeria should work with its development partners and the private sector to drive investments in infrastructure, which is required to boost productivity. Some of the infrastructure challenges include poor electricity access, weak public transportation, inadequate internet connectivity, and so on. In addition to increased productivity, such investments will create construction-related jobs and reduce the cost of doing business.

Other sectors with job creation capacity include Information and Communications Technology (ICT), agriculture, hospitality, and entertainment. Agriculture, for instance, requires synergy between farm and non-farm activities. Farming activities, with the aid of innovation, can boost labour productivity in the sector. Some of the emerging innovation platforms in Africa include Hello Tractor, a tractor co-sharing platform in Nigeria; AgriEdge, a Moroccan platform targeted at smallholder farmers; Promagric, a platform using Artificial Intelligence to diagnose crop diseases; Flamingoo Foods, a Tanzanian start-up using satellite technology to improve food distribution, etc. There are opportunities in non-farm agriculture-dependent jobs such as processing, packaging, transportation, distribution, marketing and service provision, and more.

Industrialisation will help reduce the unemployment rate in Nigeria. The capacity to produce and satisfy the needs of such a large population will put millions of Nigerians to work. However, Nigeria’s industrial capacity and utilisation rate have underperformed for decades. The industrial capacity utilisation averaged at 56.8 percent in 2019, down from 57.75 percent in 2018 (Manufacturers Association of Nigeria, as cited in Anudu, 2020). The challenges to increased capacity utilisation include weak access to credit, poor infrastructure, underdeveloped technology, high preference for foreign goods, weak institutions, and a poorly industrial skilled labour force (Omenyi, 2017).

The government must pay attention to the supply side of skills development. The policies should focus on improving education and training to enhance the employability and productivity of individuals. A first step would involve conducting a skills-gap assessment exercise through the use of quantitative and qualitative methods to understand what skills the market needs. The information should inform the design of teacher training programmes, changes to classroom learning methods, and the school curricula. Among workers aged 15–24, only 59 percent of women are literate compared to 71 percent of men (World Bank, 2019). Thus, teacher training programs should be strengthened to ensure, at least, primary and secondary education level literacy and numeracy among the youth (Runde and Hammond, 2018).

Employers around the globe seek young people with transferable skills. According to the British Council (2014), country studies indicate that the preferred skills include language ability, resilience, management, responsibility, self-motivation, etc. Therefore, educational institutions should work closely with the private sector to understand the needs of the market and redesign the learning methods.

The school curricula should encompass the promotion of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). This route can serve as an alternative to the typical four-year degree or be targeted at early school drop-outs. It is imperative to coordinate such programmes with the private sector to align them with the needs of the industry. For instance, Brazil’s vocational training programme, PRONATEC, trained about 8.8 million people between 2011 and 2014. It has 2,800 vocational training institutions that train over 700,000 people annually (Runde and Hammond, 2018). Likewise, Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (which are top European performers in tackling youth unemployment) have achieved results through a ‘dual-system’ that combines formal vocational schooling and on-the-job training. According to the World Economic Forum, they have strengthened ‘pre-apprenticeship’ transition systems, targeting potential school drop-outs.

The government of Nigeria must encourage entrepreneurship as a route to job creation and economic progress. Entrepreneurship should be a core course on the school curriculum, including programmes or workshops that allow students to interface with established entrepreneurs and gain practical experience. With entrepreneurship, the job does not stop at creating start-ups but continues through supporting them as they scale up so they can reach their job-creating potential. Part of this involves creating an “ecosystem” that brings together start-ups, mentors, investors, and government bodies, among others. This is the responsibility of the government. For instance, Startup India was introduced by the Indian government to provide financial support, networking opportunities, information access, etc. to start-ups.

Furthermore, the government must create a favourable environment for entrepreneurship by providing funding, introducing attractive tax incentives, simplifying regulations for starting a business, and many more. Robust engagements with established and prospective entrepreneurs in the country enable better targeting of these interventions. The recently introduced National Youth Investment Fund is a good start. The success depends on the intellectual rigour that will go into the design of the implementation. Similarly, the private sector must be encouraged to invest in capacity development and technical assistance, mentoring programmes, and so on.

Unresolved, Nigeria’s youth unemployment may become its death knell with increased poverty, escalating insecurity, and migration of talent to other more conducive climes. Above all, it constitutes a terrible waste of the country’s greatest assets for growth and development; the youth. The government must pilot a renewed multisectoral approach to ensure the Nigerian youth has access to jobs and opportunities. There is no way to avoid dealing with this challenge.